Köken Ergun: ‘In Turkey, the image of the soldier has been victimised by Erdoğan’

The Turkish film-maker talks about his 2005 video I, Soldier, and its relevance to the political situation in his country today

by LISA MORAVEC

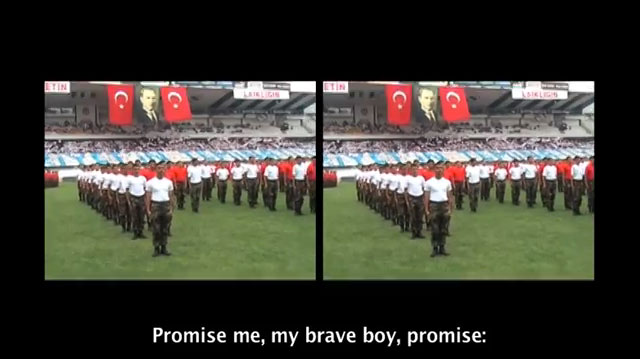

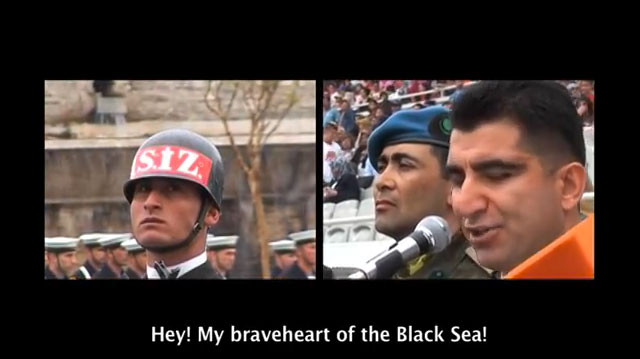

Much has happened since Documenta 14 closed in Kassel in mid-September and before that in Athens. The financial overspending of €5.4m (£4.8m, $6.3m), according to the independent PriceWaterhouseCoopers report, was critically discussed in the press, leading to Documenta’s CEO, Annette Kulenkampff, stepping down. Despite the sensational international and local press coverage, some of the artworks exhibited at Documenta reflect the sociopolitical issues that the ambitious show tackled. One of these is Köken Ergun’s two-channel video I, Soldier (Ben Askerim) from 2005. It is a poetic documentary of Turkey’s National Youth and Sports Day, an event that, from 1919, has been held every year on 19 May to mark the anniversary of the beginning of the Turkish War of Independence led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk. Today, the nationwide celebration includes dancing, marching, and speeches in streets and public squares; previously, members of the military and schoolchildren used to perform for the Turkish people inside large national stadiums.

In 2014, President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan ended the tradition of celebrating this event inside enclosed stadiums, and limited the celebration to open public spaces. I, Soldier, which belongs to Greece’s National Museum of Contemporary Art (known as EMST), was one of the rare videos exhibited at the Fridericianum to directly address issues that aligned artistic expression with national politics. In light of the failed coup in Turkey in 2016 and the strikingly grandiose celebration of the Turkish Republic Day on 29 October in 2017 outside of national stadiums, Ergun’s visually powerful documentary from 2005 opens up a space for a reflection on Turkish politics and the image of the military that goes beyond the framework of this year’s Documenta.

Lisa Moravec: Can you tell me more about the spectacular national celebration in Turkey that your work I, Soldier documents and how you became interested in it?

Köken Ergun: In 2005, I felt the need to record the annual 19 May celebration in Istanbul. Each city in Turkey used to stage its own celebration at a local stadium. High school students chosen from one school in that city produced these performances. Some of these schools were civilian and some were military. For this piece, I chose to focus on the performance of the military school in Istanbul. During my high school years, I was never selected to take part in these celebrations but, as civilian students, we were subject to patriotic poetry or marches, especially at the beginning or ending of the school week. I’ve always observed these scenes and found them too nationalistic and too macho. When I got older and was no longer a student, I looked back at it and “exorcised” my trauma of the republican education system by making a work about it. [The Turkish curator Vasıf Kortun used the term “exorcism” to describe Ergun’s work.]

Köken Ergun. I, Soldier (Ben Askerim), 2005 (video still). Two-channel-video. © Köken Ergun.

LM: What exactly fascinated you about the athletic and ritual exercises performed by members of the Turkish military and pupils? Was it the extent to which they had been disciplined in order to perform skilled bodily exercises? Or was it more the controlled state mechanism within which they performed?

KE: Both. In nation states, the so-called “national education system” facilitates the turning of young people into citizens, and I think I had a problem with this doctrine when I was subjected to it. With this work, I wanted to show this general issue, and my personal problem with it, to a wider public.

LM: How was I, Soldier perceived in Turkey?

KE: I debuted the work in 2005 as part of the Hospitality Zone exhibition at the 9th Istanbul Biennial, which was curated by Halil Altindere within Charles Esche’s and Vasif Kortun’s biennial concept. The reactions there were ambiguous, as in any other country where I showed it. Some thought that I was supporting the military, some thought I was criticising it. I think this is the strength of the work because different audiences are differently attached to it. I obviously liked something about the ceremony, but I also carefully criticised it. Patriotic audiences usually look at this work with love. They say: “Wow, you show our soldiers very well.” Audiences that are critical of the state, the nation and the military look at it differently.

Köken Ergun. I, Soldier (Ben Askerim), 2005 (video still). Two-channel-video. © Köken Ergun.

LM: That is an interesting point. When I watched I, Soldier for the first time, in June at Documenta, it was the fine and powerful accord between the visuals and the sound that attracted me to it, although the subject matter is clearly disturbing. When was the work first presented outside Turkey and what reactions did it receive internationally?

KE: The video was first screened at the Oberhausen Short Film Festival in Germany and then at various other film festivals. I received a few awards for it. The reactions from the audience there were similar to those in Turkey.

LM: And then Greece’s National Museum of Contemporary Art in Athens (EMST) bought the work?

KE: Yes, that must have been in 2010.

LM: Let’s speak a bit more about Turkey, your home country. You were born in Istanbul in 1976 and grew up there, you studied there and in London, and now you are working on a PhD project at the Freie Universität in Berlin while living in Istanbul. When you try to recall the political climate in 2005, the year you made the work, in what way do you see it has changed? I don’t know if you attended the National Youth Ceremony each year, but perhaps you can nonetheless talk about how people’s stance towards the military and its function as a controlling state mechanism has changed over time.

KE: In 2005, the military was still a very important part of the state. It was not a military state per se. Rather, “the deep state” – that’s what we call it here – was operated within and with the military. Erdoğan came to power in 2002 as Turkey’s prime minister; he became president in 2014 with the promise that he would replace the military presence with a more participatory democracy. Many people were happy about him coming to power, but his promises did not materialise immediately. At the time when making this piece, the military was still strong and I was worried that I could become the target of the military, but that didn’t happen. I was, however, selective about where and when to show the video in Turkey. The context of the Istanbul Biennale was a more or less protected space, but, for example, I did not allow the national TV channel to broadcast I, Soldier.

Köken Ergun. I, Soldier (Ben Askerim), 2005 (video still). Two-channel-video. © Köken Ergun.

LM: How has people’s approach towards the government, and consequently towards their belief in soldiers, changed since Erdoğan came to power in 2002?

KE: First, Erdoğan systematically started to work against the military. He limited its power in favour of democratic reforms. But gradually, he took over all the power in the system and trashed all the democratic reforms he had previously put in place. He now controls the judiciary and the army and the parliament and the police force, etc. In other words, he became all the things that he stood against before. This created a feeling of nostalgia among the public, a longing for the army. After all, a large percentage of the Turkish people were brought up with the idea that the army is the guarantor of a secular nation. These people are now joined by those who had previously been critical of the army and welcomed Erdoğan’s strategy of getting rid of it, but have since changed their minds after he took on the role of the army. So, now, many Turkish people, in fact, see the military as a hope for salvation from our current president.

Last year, a failed military coup against Erdoğan took place and that has brought the military and “the soldier” as a concept back into the public debate. In that sense, I, Soldier is really a contemporary work. When I made it, of course, I could not know that a military coup would happen in 2016, but I must have felt something about the continuity of the image of the soldier. This is a concept that is so heavily embedded within the Turkish culture that it cannot be erased easily. It is important to point out that, after Documenta 14 ended, Erdoğan unexpectedly declared himself the follower of Atatürk, and this October he staged a Republic Day celebration in an exaggerated way such as he had never done before. So we might also expect a comeback of other big national ceremonies, such as the National Youth and Sports ceremony taking place again inside large stadiums.

Köken Ergun. I, Soldier (Ben Askerim), 2005 (video still). Two-channel-video. © Köken Ergun.

LM: In light of this very recent event that reinforced the idea of the Turkish Republic, let’s talk more about the changing role and power of the soldier and the military in Turkey. In putting an end to the countrywide celebration of the National Youth and Sports day, Erdoğan simultaneously diminished the imaginative and iconic power of the soldier – a powerful state-embedded icon – and that of the military as a whole, to make it clear that sociopolitical issues are changing.

KE: Erdoğan first wanted to get rid of the ceremonies because he saw them as belonging to the old republic. He did have an issue with the public image of the army, that’s for sure, and he wanted to put it under his control. So, he had to erase its image from the public memory to become it. He promised people that he would release them from the power of the military and bring them democracy, but, in time, he did just the opposite. He took on all the power himself. By now, we can see his ultimate greed and vanity. Although Erdoğan already controls all the state mechanisms, he still wants more, and this will not end. The public knows that he wants to stay in power to avoid being put on trial, because as soon as he is down, they think he will be judged for the crimes he committed. I think this is exactly why he now appears to be supporting the fundamentals of the Turkish republic. He realised that his Islamist tendencies have not given him enough votes. Now he plays in the middle field, tries to please everyone, and perhaps to avoid a harsher sentence if he is ever put on trial.

LM: Are you familiar with the black-and-white images of the sports parades that took place in Moscow under Stalin’s rule in 1936 in Red Square? Alexander Rodchenko took some photographs of the parade at the moment in time when modern sports came into being, and when Stalin ordered the parade to take place annually. This was also the time when Leni Riefenstahl made her propaganda film that documented the Nazi Party Congress in Nuremberg in 1935, which were followed by her two Olympia films. Interestingly, the Soviet sports parades started to take place about at the same time as the Turkish ceremonies. In Russia, they were invented to create a collective feeling of togetherness and to connect the people with national politics – the party in power – especially with the leader of the Soviet Union, Joseph Stalin from the late 1920s until his death in 1953.

KE: That was also what Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish republic, tried to do when he created his nation state in 1923 after the Ottoman Empire dissolved. He borrowed some concepts from the Soviet model. Following his death, his republican party, which ruled Turkey under the single party system until 1945, applied these concepts and forms to the National Youth and Sports Day ceremonies. They looked at the nation-building model of the Soviets and the Nazis and copied some of their ritual forms. That is why my work I, Soldier can be perceived as reminiscent of Rodchenko’s and Leni Riefenstahl’s work.

LM: Here, I think it is also important to point out that, when you look back at the very first parades in Russia and the reason for which they were invented, it becomes obvious that the National Youth and Sports Day celebration was ended much later in Turkey.

KE: Yes, and, furthermore, the people who hate Erdoğan – as the last referendum has shown, we are talking here about nearly 50% of the population – are somewhat nostalgic about the sort of stability the army gave them. These people empathise with military coups and would like to see the military receiving some of its powers back. This is ridiculous, but it shows how desperate they are with the current political situation. I think that their hope for another coup probably goes back to their lost hope of having free elections under Erdoğan. And in this regard, a new image of the soldier starts to emerge. Under the current state of emergency, anyone sympathising with the military coup can be labelled a terrorist, so people who are supportive of the military are discreet now. But if they were given a chance, they would not hesitate to verbalise or visualise their worship of the soldier cult.

LM: As the Turkish military has lost its official powers, what do you think a new public image of the Turkish soldier could look like when taking into consideration the advancing techniques of war, such as the usage of drones and robots. Are the physically skilled soldiers that we are familiar with becoming more and more useless?

KE: That’s difficult to say. In Turkey, we could now say that the image of the soldier has been victimised by Erdoğan. Even in recent opinion polls, when asked who they trust the most – politicians, intellectuals, or the army – a large number of people still answer the army. I think part of this goes back to Erdoğan’s victimisation of the army, first by taking some of its members to court during the Ergenekon trials of 2008-10 and then by declaring them the suspects of the failed coup attempt against him in 2016. However, we still don’t know who was behind the coup. Many people don’t think the army did it. They think it was misused by the Gülen community, who have planted their own men into the army for more than 30 years in rather sinister ways. This disbelief seems to foster a nostalgic feeling for the army that Atatürk founded. He was a soldier himself. In fact, some opponents of Erdoğan regard themselves as “Atatürk’s soldiers”. So I think the contemporaneous public image of the Turkish soldier is in itself reminiscent of the idea of the soldier during Atatürk’s reign.

https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/koken-ergun-interview-i-soldier

Köken Ergun, Mari Spirito, and Yulia Aksenova in conversation about Young Turks

Interview March 11, 2016

Mari Spirito: OK, let’s get right into it: what are your earliest memories of the Turkish Olympics? I remember you mentioning them a long time ago.

Köken Ergun: It was in 2008. I had already been hearing bits and pieces about the Turkish Olympics before then, but a certain performance from that year’s Olympics shared on Facebook caught my attention. A Mongolian student was reading a highly nationalistic Turkish poem in front of a large audience with prominent Turkish politicians at the time (who are still around) and the so-called “religious” middle class.

At first, I thought how much this related to my 2006 work The Flag. That film focused on a schoolgirl reading a nationalist poem at a national day ceremony in a stadium, again to a massive crowd with politicians and army generals. I didn’t think of making a work about it at that time, but more and more clips started coming up on Facebook and other social media platforms. Senegalese students doing folk dances from western Turkey, Thai students performing a rare halay dance from the Kurdish region, an Albanian student singing a famous pop song from the time, you name it.

Among my social circle there was a kind of ironic approach to the Olympics, almost looking down on them. I cannot blame them because some of these clips appeared quite funny and even ridiculous. People would also ask with disbelief, “Are there really so many Turkish schools in the world?” or “When did that happen and how on earth?” You see, we grew up with a certain inferiority complex; a regular Turkish citizen would not have imagined Turkey being able to establish such a huge global network. But obviously there were a large number of people who actually believed in it.

MS: How have your feelings about the Olympics and the Turkish schools changed for you from then to now, after all these experiences and research?

KE: As I became more interested in the schools and how they came into being, I also became aware of the expansionist policies of Turkey. I inquired deeper into the Gülen community, who opened these schools and its complicated links to the Turkish state. By that time the Ergenekon trials had already started in Turkey and we were all hearing more and more about the collaboration of this community with Erdoğan’s government. It became obvious and public that they were working hand in hand in many fields, not only for the global spread of Turkish schools but also in domestic politics. Secular circles were looking at both of them with both remorse and anxiety, so the polarization of the society had already started back then. Amidst this polarized social atmosphere I neutralized myself to all sides and embarked on a wider research about the history of colonialism, charity, missionaries, Turkish foreign policy, World’s Fairs, religion, etc. Some of the books I read during this time are available in a special section of Garage Library now So I saw the Turkish Olympics no longer as an absurdity, but the tip of the iceberg. This is also when I started to correspond with anthropologists and historians. For example I have learned a lot from Ayşe Çavdar, who helped us shape the lecture series for this exhibition. These talks will give us a wider perspective into all these topics that eventually relate to my artwork.

Yulia Aksenova: We are doing this project in a difficult time. Although it was planned in 2013, when nothing presaged political turmoil between Russia and Turkey, today the situation is more complicated, which not only impacted the production process, but may influence the context in which the exhibition, as well as your work in general, is viewed. I think today it is really important to clarify your position as an artist who, on the one hand works with political issues, and on the other retains a critical distance toward them. Is this correct?

KE: Yes, very. Personally, maintaining a certain distance allows me to understand things better. In turn, it also allows me to do something that is more universal and permanent.

The author of any representation, let’s say the artist, has a direct ethical responsibility toward his/her topic and also his/her subjects. This ethical responsibility is not to try to establish total objectivity, which is futile anyway. It is more about knowing your subject close enough to bringing his/her voice to the world in a just way. In order to facilitate this flow, the artist should be very sensitive about the environment—both social and political—in which the subject lives. This can be achieved best by having a subtle approach to all sides of the story; to be able to insert yourself into it first and then hover above it and look at it from far away. That distance should not be too far to detach completely but also far enough to maintain your own personal integrity and perspective. So you can make your own judgment, and not get too attached to the “field” as they say in anthropology— basically your subject(s). This way you can, or at least I can, construct a representation of something that shows the kind of “unexpected” nuances within big narratives.

Politics is a big narrative, for example, and Young Turks is dealing with that kind of big narrative, or let’s say phenomenon. That is what the Gülen community and the Turkish state do in the world. Of course, I am very informed about that but my focus is on the stories or attitudes of individuals who are small parts of the larger phenomenon—individuals who make up this highly complex community. The people who are not heard in general discussions about this phenomenon. We have a lot to learn from them, whether we agree or not.

That’s also why I chose Göran Olsson’s film Concerning Violence that goes with the exhibition. Olsson juxtaposed a key text on post-colonial theory with personal stories. As explosive and interesting as Frantz Fanon’s text may be, it is his own narrative on a huge topic and does not include the voices of the subjects that are written about. We hear him (Fanon) speaking, not them. But his text falls into a better place in Concerning Violence, when actual interviews with the “real” colonizers are shown together with it.

MS: What are your main concerns in relation to neocolonialist expansion, not just by Turkey, but any country?

KE: As long as there is the interplay of power between people there will be expansions and contractions. The Phoenicians were not the first ones to expand back in 900 BC and Turkey will not be the last. And it looks like all expansionist powers or attitudes are following each other, building on top of each other.

The first reaction I had when I actually went to the Turkish Olympics back in 2012 was to think how much it resembled the World’s Fairs of the turn of the century. The interaction between the Turkish audience and visiting students at their country booths was pretty similar to what we can read about the interaction between American fairgoers and Filipino “displays” at the St. Louis World’s Fair (1904) or the French audience and their African “guests” at the Paris Expo (1889). So the expansionist attitude cannot only be blamed on states. It is also the people who endorse it. This is what I wanted to show inYoung Turks.

Also, we are seeing a surge in the expansion of religious communities like the Gülen community. They also build on the history of previous religious communities opening up to the world of the “other.” The Jesuits are an example from Christianity. Ayşe Çavdar also sees historical links between the traveling dervishes of the 14th century and the current global spread of Turkish schools.

YA: In your work you explore the role of ritual and methods of representing the identities of ethnic and religious communities. Could you explain how this project coincides with your research interests? In your opinion, does it manifest a new phase in your artistic practice?

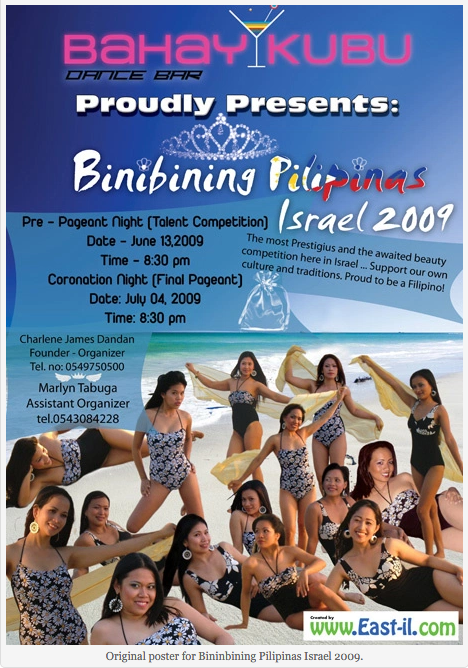

KE: I couldn’t call it a new phase in my practice. I think Young Turks is a continuation of the direction I have had since making earlier works about other social groups, such as the Turkish immigrants in WEDDING and the Filipino guest workers in Israel in Binibining Promised Land. So the same thread continues but the focus is different. The people who are the subject of the work designate the process and shape of the work. They also change me and how I shoot or edit the work.

In time, I got more and more interested in individual stories within the mass. For example in WEDDING I didn’t focus on the individuals but the group dynamics within the mass. I was amazed at what they do and achieve, maybe jealous of them because I grew up as an individual with no such rituals. Then in Binibining Promised Land I included personal interviews into the project, but they were shown on separate monitors. Young Turks is the first time I inserted the personal interviews into the main film.

As far as ritual is concerned, Young Turks is also about a ritual but a new one. The Turkish Olympics is only 13 years old. That might sound too young to call it a ritual, but it could be the beginnings of the making of a ritual. So the audience and I might be witnessing the making of history.

MS: Do you think that the Turkey that exists in the minds of the young students around the world actually exists? Do any of these students who come for the Olympics leave disenchanted?

KE: Almost all of the students I talked to left Turkey completely enchanted. Among the students of Turkish schools in Kenya and Indonesia there is an enormous love of everything Turkish. You also see this in the general public too. Private cars are decorated with logos of Turkey or Turkish university stickers, like those you used to see of Harvard University on the back of cars in Turkey in the ‘80s. The US is not as trendy. Turkish Airlines opens more and more direct flights between İstanbul and African destinations and many passengers connect to the rest of the world from there. This is more than transportation or profit, it means a lot to the African continent. So they embrace Turkey and Turkey acts as “soft power.” This is why we installed a world map in this exhibition, to visualize Turkey’s expansion. But this could be the expansion of any country. In fact, I see this map as a symbol of any expansionist strategy. Maps are important because states or ideologies try to shape the world by making their own maps. Almost no map is objective. There are also books about this in our selection at Garage Library.

Coming back to your question, we should remember that these are teenagers. It’s a relatively early period of life to construct a critical approach. Moreover, these kids are sent by their parents to these schools—most Turkish schools in Africa are top rated—hoping that they will have a bright future. A bright future in Africa mostly means going abroad. Maybe it’s better if I end with a quotation from one of the interviews in the exhibition. This is Erkana speaking, 15 years old, from the Turkish School in Nairobi:

– Have you ever been to Turkey before?

– No, but I’m looking forward to it. I know it will be a good experience for me. As a Kenyan, I’m going to get to know new people outside this world. Most of the time, we only get to know people when they come to the school. But now we are going out of the school so that we will get to know new people. It is nice.

– Do you think you will go to Istanbul?

– Yes. I’m looking forward to that because personally I love Istanbul. It is a great city. Though we know we will be in Ankara for quite some time, I’m praying that we go to Istanbul because the city is beautiful and I like it.

– What do you know about Istanbul?

– I know about the bridge that connects Asia and Europe I’m looking forward to going to that bridge.

MS: You are able to walk a very fine line of balancing multiple perspectives in most of your work, but more so in Young Turks. Is this intentional? Is this something you are conscious of, and if so, how do you do it?

KE: It’s part of me, I guess. I always want to see all sides of everything. That might even be the reason why I do multi-channel films. I like that multiplicity and the ability to see things from different angles. In my personal life, I like to be surrounded by many people, have friends from different walks of life all over the world and compose a life with the interactions I have with all of them. This is probably why I am doing work about social groups, or let’s say social bonding.

As far as the work goes, it just happens naturally too, because any work I do is directly informed by my personality. I always became good friends with the people whom I met during the process of my work. And it usually happens very quickly. I am now almost a Filipino for my Filipino friends around the world, the Shiite community in Istanbul accepts me as one of them—they even gave me an honorary prize at an Ashura ceremony. Even in Young Turks, I became friends with the teachers in the school. I say “even” because they are a relatively closed society and I have to confess that I started the work with reservations about them. Because the Gülen community has interfered with Turkish politics and the judicial system for a long time behind the scenes and they have developed a bad reputation. But I loved the teachers and we spent a great time together outside of filming. We became like normal friends. Only when I met them did I understand that this is not a homogenous community. Not all the individuals in it can be held responsible for all the deeds of the community, good or bad.

THIS HAS BEEN OUR DREAM

Conversation: Köken Ergun with Özge Ersoy

Köken Ergun’s work, which I have been following for the last ten years, has always pushed me to question how the camera intervenes into an event and change the social dynamics. After all, how does the camera record the conditions of belonging or even alter them? Köken and I met a few times in the last year and recorded our conversations. Below is an edited version of these extensive discussions. —Ö.E.

Özge: Let’s start with your most recent project Young Turks (2013–2015) to discuss how your agency as an artist with a recording camera has changed since I, Soldier, the two-channel video you made in 2006. As of this moment, Young Turks is exhibited at Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow, where the installation is centered around a two-channel film projection. [1] In this film, you look at students and teachers who are part of an international network of Turkish schools—which are active in more than 100 countries worldwide—, and document the Turkish Language Olympics, organized back in Turkey, where students from these schools compete in reciting poems and singing songs in Turkish, or performing Turkish folk dances, etc.

For me, there are two conceptual threads in the video. The first one starts with foreign children who prepare for the Olympics in their home country. It continues with the teachers who assist them, the schools that facilitate these interactions, and finally we have you, looking at this particular structure. I think you have a rather distant, observant role here—it’s not easy to figure out your own position about the Turkish schools, their de facto diplomatic mission, their soft power, or what constitutes a culture that is “typically Turkish” for that matter. The second thread starts with foreign children, as well. It continues with the audience who watch these children performing on stage, and ends with you watching the audience with your camera. I believe your interest lies in the multiple acts of watching rather than the politics of this structure.

Köken: The Turkish schools of the Gülen community are part of an expansionist project, and the Olympics are the popular face of this expansion. [2] The Olympics promote activities of the Turkish schools to the Turkish public who are expected to support their expansion in return. The Olympics are also an extension of universal expositions that started in the 19th century—but a smaller and rudimentary version of it. Think about it: This is the opportunity for non-passport holding middle class citizens to see the rest of the world, just like how it was with the universal expositions in the past.

At the Olympics in Izmir, Turkey, the interplay between curiosity and proximity results in most interesting interactions between the host and the “others.” You see women squeeze Ugandan boys’ cheeks, congratulating them for speaking Turkish eloquently, or applause for their folk dance moves, etc. This is what I look at in this project—how people interact and show their feelings in these gatherings. I’m not interested in documenting how the Gülen Movement functions or how Turkey pursues expansionist politics, but rather how these projects are consumed or interpreted by ordinary people. This is why I have a lot of close-ups of the audience as well as fairgoers. What I’m interested in is the aesthetics of this expansionist project.

Köken Ergun, Young Turks, 2013-15. Two channel video installation with sound. Courtesy of the artist.

Özge: The audience in Izmir consists mostly of women. In one of the peak moments of the film, your camera captures a middle-aged woman who holds a sign that reads, “This has been our dream.” She has tears in her eyes and a euphoric expression in her face. She seems to take the ownership of the Olympics, she’s proud, and it looks like she’s been waiting for that moment for a while.

Köken: She held that sign for almost two hours, crying silently. No one gave her strange looks. What is it that she’s so proud of? I’m not sure if it’s only about Ugandan boys performing Turkish folkloric dances. It feels to me that she is almost “religiously” proud of a bigger narrative carried on by her country. Holding that banner throughout the event, she must have felt like a flagbearer of this expansionism.

But when you talk to people who work for the Gülen schools abroad, you realize they want to have a softer and friendlier attitude compared to the old colonial powers. In Kenya you have the Austrian School, the French School, but Gülen schools are not called Turkish schools; the one I filmed in Nairobi is called the Light Academy for example. Some teachers are aware of the criticism towards them, that there is a somewhat colonial agenda behind their schools, but they emphasize that they’re against such policy or practice. I assume that popular activities like the Turkish Olympics are made in order to promote this soft approach/face. But whether it transfers to the outside world like that is another matter.

There is an enormous organization behind the Olympics. Hundreds of people work for it throughout the year. Art directors travel to a different country every week, musicians record songs with big orchestras, and teachers produce custom-made choreographies for students/performers. On the one hand, you have this extremely rigorous structure in order to highlight a soft and universalist approach. On the other hand, you have the reaction of the audience back in Turkey, who receives these efforts, I believe, in a completely different way. I’m interested in the interplay between these two and the bizarre spectacle it produces.

In the video, I show people wandering around the fair, holding taxidermized crocodiles, smelling vanilla beans—items that are brought from far away countries where the Turkish schools have reached, sometimes even before the Turkish embassies. As I said before, this is not dissimilar to the interactions at the 19th century universal expositions. That said, in Izmir, you don’t see a human “zoo” where people throw bananas and nuts at foreign students—there’s a rather new type of interaction here: People take zillions of selfies with these kids. There’s a moment in the film where you hear an announcement that says, “Please don’t touch African children too much,” while they’re trying to take photographs with them. This is exactly what I’m looking at—how the middle-class Turks deal with the rest of the world, how they struggle with their inferiority complex, and how all of this turns into a spectacle.

Köken Ergun, Young Turks, 2013-15. Two channel video installation with sound. Courtesy of the artist.

Özge: The reception of the Olympics is fragmented through different cameras, including your shaky hand camera, your Director of Photography’s camera on a tripod, the camera of the organization on the crane, and hundreds of cell phones that record what’s happening on the stage at the same time. I wonder where you position yourself in this network of the act of watching. After all, you focus on the audience but you still want your DOP to film the stage.

Köken: Yes, the Olympics are highly documented public events. The multiplicity of these documentations makes me inquire about my own position with the camera in particular and the position of the arts in life in general. The more I make films, the more I question this position. But, nevertheless, I remain to be of the many cameras in any event I shoot. Maybe in the next project, I might turn the camera directly to myself to challenge this. But at the moment I choose to document and to represent.

In Young Turks, I chose to work with two synchronized cameras and later to show them as a two-channel synchronized video. My camera was recording the audience’s reactions when they’re watching the performance on stage, documented by another camera on a tripod. There was a moment when the presenter on the stage said, “We are so grateful to you because you sent your sons from all over Anatolia to Africa.” This is precisely where I wanted to see how people had silent tears in their eyes—this is the detail I’m looking for. And to be able to represent this moment to the audience I needed to show them both the action and the reaction, at the same time.

In the future, if I want to challenge “representation” all together, I will probably look for a different approach, and maybe that approach will be omitting the camera completely.

Özge: It’s tempting to think that your interest in the Olympics is related to the symbols, images, and materials produced as part of a ritual, which is a recurring theme in your practice. If we go back to your earlier videos, in I, Soldier (2005) and The Flag (2006), you focus on public ceremonies, documenting the rituals of strong, established institutions such as the state or the armed forces. In these works, you are quite distanced from your subject; you rather observe them from a distance. I think that the way you inquire about rituals changes after these works. You turn your camera to immigrants’ weddings in Berlin (Wedding, 2006–08), Filipinos in Tel Aviv (Binibining Promised Land, 2009–10), Caferi Shiites in Istanbul (Ashura, 2010–12), and most recently the Turkish Olympics (Young Turks). The common denominator is that these groups are somehow marginalized in the larger community they live in, and that you spend time with them, following their respective rituals for months. How do you think your perception of rituals has changed over time, through these works?

Köken: For me, rituals are the key to understand society. But my interest in rituals started with an attempt to understand myself. Let me start with I, Soldier (2005, 7 min.). I shot this video at a stadium in Istanbul on May 19th, the National Day for Youth and Sports in Turkey. It looks like a simple documentation of the ceremonies but I believe there’s a sense of revenge and resistance against the state discourse and discipline in this video. I was 28 years old at that time, and I was desperately trying to say, “I’m not one of you.” In the video, there are long moments of close-ups of a high-ranking soldier’s face. Why did I make this choice? I can’t answer it easily but it might have to do with my fascination with macho attitudes in men, it might have to do with me being gay. But at that time, I didn’t realize that there was something to do with my own emotions.

There was a similar sense of revenge in The Flag (2006, 9 min.) that I shot on April 23rd, the National Sovereignty and Children’s Day. This time, there was a strategy behind it, in the sense that I wanted to have a second national celebration to complement I, Soldier. So it was a professional decision, not an intuitive one—it was the first time that I aestheticized my experience. I see this as the first moment of my “degeneration,” as this was the attitude of a professional artist. The word “degeneration” doesn’t have to have negative connotations. I mean that with this decision I included myself into the system of artistic production and started to take decisions somewhat informed by the norms of the art world, as I perceive it.

After I finished these videos, I moved to Berlin and something changed in me there. Although I spent a lot of time living abroad before, mainly in New York and in London, they were not permanent stays, but my moving to Berlin was to stay and for the very first time in my life I felt like a foreigner, a guest, a being without a country. I felt what we call gurbet for the first time. [3] So when I wanted to make a new work there, I intuitively looked at an immigrant community. I started going to weddings of Turkish and Kurdish people there, and in the end I produced a three-channel video installation. This was a professional decision too, due to my ongoing fascination with Eija Lissa Ahtila’s work, which I saw for the first time at Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta in 2002. My background is theater, so I was also interested in the theatricality, in the idea of stage, in dance, in make-up, in the movement that dominates these celebrations.

The theme of gurbet continued when I started going back and forth to the Levant. [4] This geography is full of dislocated people. I encountered the Filipino community in Lebanon for the first time. I made a work about them in Israel, titledBinibining Promised Land (2009–11, 38 min.). It was while doing this project that I became aware of the fact that I wasn’t only making work about a certain social group, which remained unseen in the greater society but also the very process of my “bonding” with that group was part of the work itself.

I was in Tel Aviv for a residency when I came across this fantastic poster of a Filipino beauty pageant to take place inside the main bus station. I immediately contacted the organizer from the phone number written on the poster, introducing myself as a filmmaker who wants to see and maybe film what they are doing. The voice on the other side of the phone just said: “Sure! Come tomorrow, my friend.” The next day I found myself at their rehearsals in an ordinary corridor of that giant complex. I just observed what they were doing without filming. An hour into the rehearsals we became “best friends.” Two hours into it, the girls invited me for dinner at their shared apartment. Three hours later we were making noodle soup at a cramped flat for a group of 50 Filipinos; all of them guest workers working all around Israel, mostly as caregivers. I was enjoying myself tremendously and felt extremely comfortable in their company. They said the same for my company. Somewhere in between I started taking photos but it was more for them to put on Facebook than for me to use them in an art project. I forgot about the film camera altogether. I think I even left it there before we went out to the church for the evening service. After that, as a larger group, we went back to the bus terminal and partied until the morning.

Then I started meeting them every Saturday afternoon—the start of their off-day—, and hanging out with them in various joints inside the bus station until Sunday afternoon when they would board buses and head of back to the cities or towns where they worked. I was also helping them to organize the beauty pageant and other events, which I documented with my camera. This footage would compose my film Binibining Promised Land. But I felt that the time I spent with them and the interaction we had was actually the most important thing. I realized that this was becoming the main characteristic of my art(istic) practice. I also thought that the audience of the film would not be able to feel that interaction between us and this was the first time I questioned representation. I thought about leaving representation altogether. In other words, leave art, because I believed that the process was more fun and satisfying than the end product—the artwork. But now I think differently. As much as the artwork about a people will not really represent that people or my experiences with them, and certainly not all of the personal transformation I lived through that process, it still has a value as something to be made and shared. In fact, all the social groups that have been subjects of my workswanted to be known and seen by a wider public. This leaves me with a sort of duty and this has to be carried out with a certain ethic that affects both sides.

Anyway, at this point in my life, I can say that rituals and the “art” that I do about them are tools for me to bond with different social groups. This enriches my life experience.

Özge: You mention that you like to become friends with the people we see in your videos, that you like to keep in touch with them after the work is finalized. For me, that type of friendship starts on an uneven base, because you have the camera in your hand, which immediately creates a power hierarchy. So I tend to find your statement a bit naïve, for lack of a better word. After all, you’re the one who selects the images, who decides on the sequence, and ultimately who shows them in a format you want, also choosing your audience. So I’d like to go back to this issue. How do you negotiate the power dynamic that the camera introduces immediately?

Köken: This is an issue that has to be evaluated case by case. What you’re saying is a generalization too. Not all interactions formed through the camera have to be selfish and calculating acts. Let me talk about Ashura (2010-2012, 20 min.) here. In this work, you see me filming some members of the Caferi community in Istanbul rehearsing for the day of Ashura when they perform a reenactment of the Battle of Karbala. However, I didn’t start this work with a camera in my hand. I first watched the Ashura rituals for some time, and then I called them to say that I wanted to meet them. We met and stayed in touch for about six months when I started building friendships with some members of the community. It was with these friends that I discussed how to best document their ceremonies, which led the way for them to invite me to their rehearsals from the beginning, a month before the day of Ashura. In the first two weeks, I went there without a camera and met many people from the neighborhood. Their religious leaders greeted me saying “You are one of us now.”When I felt it was the right time to shoot, I asked them if I could bring my camera with me. Some were surprised, and some complained about me not bringing my camera beforehand. They also wanted to be seen by other people. I believe I have built that relationship of trust through my personal experience. In other words, I created an ethical proximity with my subjects through interactive cognition, not with a general idea of ethics that I carried from outside.

Köken Ergun, Ashura, 2010-2012. Three channel video installation with sound. Courtesy of the artist.

Özge: I’m also curious about how the events you record change with your presence there with your camera. I think there’s a breaking point in Ashura where you move away from the event, the rehearsal, and turn your camera to the backstage. Something crucial happens here. A young man looks directly into the camera and asks you, “Do I look handsome, brother?” Here you make your presence visible to the viewer for the first time.

Köken: I think that moment is the climax of Ashura. Something really shifts when the camera no longer produces a distance between the subject and myself. At that moment we are almost deleting the camera from our experience: I’m no longer the director or the artist but someone close to them, an insider, and also someone from the group I’m creating a representation of. The artist as the tool of representation is no longer instrumentalized. There is always a way to make the camera disappear.

Özge: I’d like to ask you how we could think about rituals with and through art forms. How could art contribute to the ways we discuss the inexhaustible need for rituals and social customs in today’s world?

Köken: I think rituals preceded culture and religion. Over time, they evolved into culture, religion and even arts. Then these broke into fractions: “our” religion, “their” religion, etc.

There is still a need for new myths and rituals, even in communities where spirituality doesn’t play an essential role in social life anymore. Some German scholars see theater as a ritual for communities where religion is no longer dominant. I agree with that. For example Wagner’s Bayreuth festival has become a ritualistic act for the followers of his mythology inspired theatre experience. Everyone who goes to Bayreuth knows the plot of The Ring by heart, and there is almost nothing new except for the interpreters. They attend the performances with a sort of spiritual commitment, to experience the performance once again and also to be in the “special,” church-like environment—the theatre that Wagner built himself. The whole experience of Bayreuth has so many codes, repetitions, rules, forms, and invariances—all characteristics of rituals. Lights go off, ouverture, act 1, intermission, long picnic lunch outside, a certain type of food eaten, certain dresses worn, etc. There are so many forms that resemble rituals in the general sense. You can even think about clubbing as one of the modern rituals, with its specific codes and repetitions. So when art looks at rituals, it is actually looking at its origins.

Özge: I’m thinking about a conversation with philosopher Boris Groys, where he says that both contemporary art and contemporary religion use the same tropes and tools, such as digital networks, performances, the principle of participation, and the combination of texts and images. [5] Both are interested in the audience, in the public sphere, and both have the claim of immortality if we think of art’s emphasis on conversation, restoration and reproduction. Do you agree with this argument?

Köken: Omar Kholeif and I discussed this previously. [6] I’m someone who believes that art and religion have more in common than arts and science. So I agree with Groys to a certain extent. But I think it’s too soon to think that the arts can turn into a religion. There are of course ritualistic aspects in the arts, such as museum-going or opera going. But when you look at the history of religions over 1,000 years, contemporary art is too young of a phenomenon to be called a religion. I think Enlightenment is a much more powerful religion in and of itself. Contemporary art could be only a small extension of that. But there are positions that challenge that view, too. I mean the position of seeing contemporary art as a secular and enlightened practice.

In 2015, I participated in an exhibition titled “Rainbow in the Dark” (curated by Sebastian Cichocki and Galit Eilat in collaboration with SALT, Istanbul). [7] The curators suggested inquiring into the power of popular religious and spiritual imagination and what kind of a role this played in artistic production in recent years. They found out that there are “religious” artists too. It was one of the rare contemporary art exhibitions that looked into religion with and without a critical approach at the same time. In fact some works were looking at the Enlightenment with a critical approach.

Özge: To me, it looks like neither religion nor contemporary arts offers salvation, but both articulate themselves around the sense of belonging—participation and forming communities. I wonder if it’s possible to build collective subjects, through either of them. Or how could contemporary art complicate the way we think about the potential of that collective subject?

Köken: There has always been a need to act collectively—religions and rituals are both ways of touching and living together. But our contemporary codes are rather individualistic. It’s a struggle to get involved in the collective. This happened in Tahrir, Tel Aviv, New York, and Istanbul, but we’re not exactly sure how to continue. That’s why it might be useful now to think about and understand the collective defined in religions. Scholar and mystic Ibn-ül Arabi changed the way I look at these issues. He likens belief to a wall and the prophets to the bricks that make it up, along with the people. I like the sense of patience and perseverance here. This is the collective attitude.

Both religion and art use abstraction: there’s a belief in and an aesthetic attachment to abstract things. Religion has been hijacked and misled to strictly organizational and rigid structures as in the case of the hierarchy of the Church in Christianity. Much of the old religions have lost their promise of a universal collectivism that had never been rigidly defined but was in fact grew pretty emotionally as well as collectively at the time. People are in search of new ways of establishing a collective. Why shouldn’t art lead the way?

January 2015–February 2016, Istanbul

Köken Ergun, I, Soldier, 2006. Two channel video installation with sound. Courtesy of the artist.

Endnotes:

[1] Developed by Garage Museum of Contemporary Art (Moscow) and Protocinema (Istanbul and New York), this exhibition is the first comprehensive presentation of the project.

[2] This primarily religious community is led by the reformist Turkish-Muslim preacher Fethullah Gülen, who has been living on a secluded compound in rural Pennsylvania since 1998 when he faced imprisonment in Turkey by the military backed judiciary. Along with a global network of schools in over 100 countries, the movement also runs a media empire and several business organizations. Since their initiation, the movement has always attempted to ally itself with the state, gradually becoming a part of the Turkish Republic’s strategy of international dominance.

[3] Absence from home, in Turkish.

[4] The Levant is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean, including Cyprus, Syria, Jordan, and Palestine, among other countries.

[5] “A Conversation Between Boris Groys and Maria Hlavajova: In the Absence of the Horizon,” The Return of Religion and Other Myths, eds. Maria Hlavajova et al. (Utrecht: BAK, 2009), 73–81.

[6] “Who’s Afraid of Religion?: Köken Ergun in conversation with Omar Kholeif” Ibraaz, 8 May 2014,www.ibraaz.org/interviews/133.

[7] For more information, see: saltonline.org/en#!/en/959/karanlikta-gokkusagi.

///

Köken Ergun (b. 1976, Istanbul) studied acting at the Istanbul University and completed his postgraduate diploma degree in Ancient Greek Literature at King’s College London, followed by an MA degree on Art History at the Bilgi University. After working with American theatre director Robert Wilson, Ergun became more involved with video and film. His multi-channel video installations have been exhibited internationally at institutions, including Palais de Tokyo, Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam, KIASMA, Digital ArtLab Tel Aviv, Casino Luxembourg, Protocinema, Wilhelm Hack Museum, SALT, and Kunsthalle Winterthur. His film works have received several awards at film festivals including the “Tiger Award for Short Film” at the 2007 Rotterdam Film Festival and the “Special Mention Prize” at the 2013 Berlinale. Ergun’s works are included in public collections such as the Centre Pompidou, the Greek National Museum of Contemporary Art, and the Kadist Foundation.

Özge Ersoy is a curator and art writer based in Istanbul. She is the program manager of collectorspace and the managing editor of m-est.org. ozgeersoy.tumblr.com

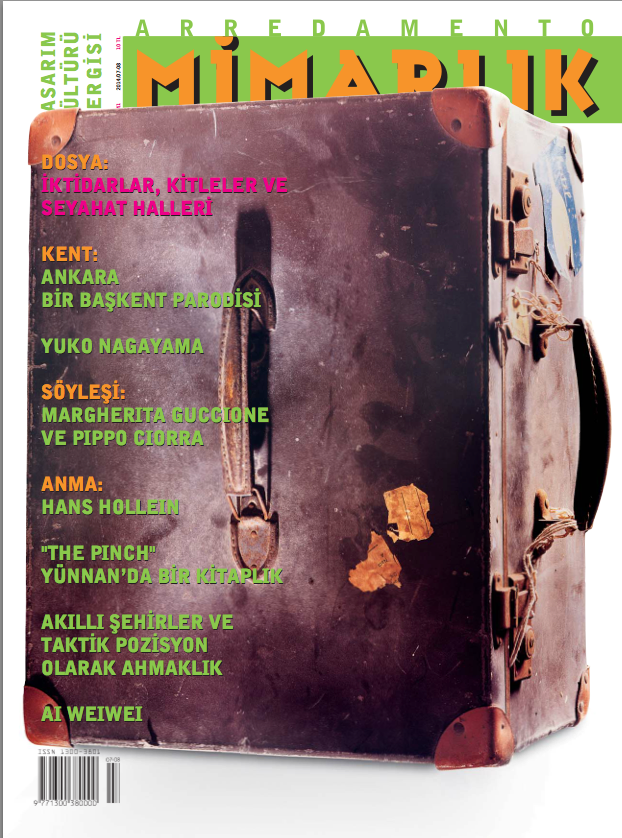

İktidarlar, Kitleler ve Seyahat halleri

5 Aralık 2013 – 16 Şubat 2014 tarihleri arasında SALT ULUS’da gerçekleştirilen KİTLE VE İKTİDAR adlı solo sergim sırasında bir dizi konuşma yapılmıştı. Konuşmalar doğrudan benim işlerimin birer okuması değil, işlerin değindiği konuların sanat dışında bir perspektif ve disiplinden irdelenmesi üzerineydi. Serginin en büyük odasında yer alan ve İsrail’de çalışan Filipinli hastabakıcı kadınların Tel Aviv otagarında yaptıkları güzellik yarışmalarını konu alan ‘Binibining Promised Land’ adlı işinden yola çıkarak mimarlık tarihçileri Doç. Dr. Elvan Altan Ergut (ODTÜ) ve Doç. Dr. Neşe Gurallar (Gazi Üniversitesi) ‘İktidarlar, Kitleler ve Seyahat Halleri’ başlığıyla bir söyleşi gerçekleştirdiler. Bu söyleşide Tel Aviv otogarında yapılan güzellik yarışmasından yola çıkılarak Ankara Otogarının tarihçesi ve güncel kullanımı üzerine konuşuldu. Konuşmanın video kaydına buradan ulaşabilirsiniz.

Bu konuşmanın ardından Gürallar ve Ergut başka akademisyenler, yazarlar ve benim de katılımıyla altı makaleden oluşan bir dosya hazırladılar. Aşağıda PDF olarak indirebileceğiniz bu dosya Arredemento Mimarlık dergisinin Temmuz/Ağustos 2014 (41) sayısında yayınlanmıştır.

PDF dosyasını görüntülemek için buraya ya da aşağıdaki resme tıklayınız.

Who’s Afraid of Religion? Köken Ergun in conversation with Omar Kholeif*

* original version on the ibraaz website with pix and video clips can be seen here

In this interview, artist Köken Ergun discusses contemporary art’s relationship to religion. The conversation raises pertinent questions, including the issue of whether the institution of contemporary art is constructed as a secular one that ghettoizes artists who explore religion and ritual in their work. Ergun discusses these complexities and contradictions by mapping out historical relationships between visual culture and religion, ultimately begging the question: has the institution of the art world become so subsuming that it has stripped artists of a particular agency?

Omar Kholeif: I want to begin by talking about religion in your work. You’ve mentioned before that you think that this is a taboo subject in contemporary art. Why do you think this is the case when nothing else seems to be off limits?

Köken Ergun: There is a very complicated relationship between contemporary art and religion and I don’t think it is being discussed enough. Once, Boris Groys came out and said contemporary art is godless. And only recently did Kaelen Wilson-Goldie write this challenging text about contemporary art’s timidity when it comes to religion.

On my part, well, first of all, it is not a taboo. But I think religion seems to be a subject that is rather absent and naturally avoided in contemporary art. I tend to look for the reasons for this in the personality of people who make or shape contemporary art. Since I started working in this field, my personal feelings and observations have been that people who are working in what we call ‘contemporary art’ are dominantly living secular lifestyles. Religion is absent in their lives, so it is probably natural that it is not that present in the vocabulary of actors in the field. On the contrary, one can argue another perspective: that it is present but rather one sided. We do see quite a few works of art that display a clear opposition to religious structures and phenomena, but do we see works that embrace religion or systems of belief?

OK: Why do you think that is?

KE: I think there is a serious disconnect between the world of contemporary art and that which we might deem to be sacred. It might be because contemporary art provenance coincides with the rise of secularism in the western world. It may be because it came about at a time when humanity almost destroyed itself in two world wars, neither of which was directly related to religion. Or is it because contemporary art – as a critical sphere – has always been reactionary to the social orders that have predominantly operated around religion?

OK: It seems that you are building up to the idea of artistic subjectivity.

KE: Aren’t artists known to be more inclined to emotional and spiritual things? If so, what makes religion and spirituality so different in the eyes of contemporary art and its artists? Why is it acceptable in particular social circles to say, ‘I am spiritual’, but not to say, ‘I am religious’? Is it because of the excess baggage religion has accumulated in the past centuries, in that it evolved from pure belief into a massive juggernaut of power structures? Should this stop us from negotiating with anything religious at all? Don’t we then betray the criticality of contemporary art, which is perhaps its most genuine character, if we relegate everything religious or everyone religious? It makes me sad to witness prejudice against religion and especially religious people within these circles.

OK: Could you give us some examples of this prejudice?

KE: For example, in Turkey and the wider Middle East where a majority of the public are not leading secular lifestyles, their artists and especially institutions of contemporary art choose to emphasize their secular nature. They do not programme exhibitions or events that could open different perspectives to such a prevailing issue in their society. Aren’t they accordingly excluding a big social group in their society? Do these institutions or actors fear stigmatization for being religious? Why do they develop such an allergy to religion or religious subjects? I think this attitude could be deemed an allergy. For example, try using the words inshallah in a catalogue text or during an installation/institutional meeting in this geography. I do, and I often get sarcastic reactions. Sometimes it is the curators who give this type of reaction, sometimes directors and other institutional workers, sometimes artists. Occasionally the question follows with an unbelieving but sympathetic smile: ‘Are you religious?’. This kind of allergic attitude to anything religious feeds from and also contributes to prejudice.

Ashura (excerpt), 2012

OK: To what extent do you feel religion is an institution, and how do you view religion’s historical relationship with art?

KE: Well, first of all I believe that religion preceded culture. Also, it had aesthetic importance. It always brought with it a certain kind of visual culture. Historically, the relationship of art and religion has always been a productive one, not counterproductive. They still mingle. We see it in Indonesia, in Muslim Java, where religious rituals – once attributed to pre-Islamic traditions and then appropriated according to Islam – gracefully blend with local puppet theatre. We see it in East Africa, where tribes continue to develop their own music and set of movements for rituals attributed to different deities, even if most are now practicing monotheist religions introduced to them by the occupying west or Arabs. The people of Bali believe that if God gave them a talent, such as a good voice, skilful hands or a good physique, they must use and display their talents as a thanksgiving to God. They do not see it as art only. It also continues to be this way in the west, in some forms of art, but those forms of art are not considered to be in the same league with contemporary arts. We are to blame for this polarization. It seems like the Enlightenment has corrupted us.

And yes, religion was probably the first institution.

OK: Do you see a difference between how religion has played a role in creative practices, or in art history, in Turkey and the wider Middle East and the western world? How do you see these two institutions colliding today – the notion of organized religion, and the contemporary art world in its global incarnation as a network of art fairs, biennials, galleries and foundations?

KE: The Enlightenment was a game changer in the relationship of arts and religion. It forced art and religion into a divorce. Today, western culture – which contemporary art is a child of – is clearly dominated by the ideas of the Enlightenment and so the divorce has its strongest effects here. Some view the Enlightenment as a religion itself. If that’s the case, one could argue that the new religion did not want the old ones to survive. But they all do, unfortunately. As I said, contemporary art can treat other forms of art in a patronizing way. In this way, it resembles both the Enlightenment and religion.

The cultural revolutions of the new nation states that occurred in our region following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire were all pivoted by a social elite that was trained in the west. Therefore, a rather late appropriation of western modernism happened here. We are still experiencing the side effects of this. Since this elite still holds key positions in the art world, whatever happened in the west after the Enlightenment – in terms of art and religion – also happened here. So contemporary art and religion are colliding today both in the so-called East and West.

OK: Is art a religion in itself, in that it tends to operate as an institution and through institutions?

KE: Contemporary art is institutionalizing at a fast and worrying pace, but this should not mean that it is a religion. I think for something to be considered a religion, what is more important than being or having an institution is how essential it is to have an unconditional belief in something abstract or something not easily explained or proven. In fact, in any given religion there is not a pressing need to define the supreme being or order, rather it is taken for granted. In this sense, science can never be a religion for example, because it is doing exactly the opposite. But art is closer to religion in that sense. This is why the pairing of art and religion seems to me more interesting than the pairing of art and science. You could say that some forms of art are religion-like, in that it has a set of rituals and devoted followers, such as opera or club music (‘God is a DJ’). But in general, art is something that developed in close contact with religion, but it is not a religion on its own. Specifically, contemporary art is unique in this way, because its distance from religion characterizes it.

OK: What kind of place does religion have in the discussion around future arts institutions, infrastructures and audiences, particularly in the MENA?

KE: It could be dealt with like any other topic. And I wish it would develop naturally and organically, because if the state, or let’s say ruling governments, starts to insert religion into this sphere, I think it would be very problematic. For example, here in Turkey the current AKP government has already hinted at something called ‘conservative arts’ indicating – perhaps – stronger state support for projects or institutions that produce art that would please their voters. But the nature of this plan (if it really is a plan) is absolutely unclear and if it involves state control over this delicate topic, then it posits immense dangers. The region is still prone to modern dictatorships, be it through a person who was democratically elected or through lineage, and if they try to dictate their way (whatever way it would be) into culture it would only be harmful to artistic production and reception, and by this I mean the audience.

On the other hand, I have been observing that most institutions in the Arab world tend to support more Arab artists. For example, Iranian or Turkish artists are not so much included in that circle. This gives a picture to the outside that Arab art institutions are primarily endorsing Sunni Arab art, which is a pity. The issue is really not about me, but I have experienced it first hand: when a curator in Dubai – where the state is the main funder of art institutions – wanted to show my work Ashura (2012), which deals with a Shiite religious ritual, it was problematic for her to programme it because anything related to Iran would be potentially seen as unfavourable. Again, when she wanted to show my work about the beauty pageants of Filipino guest workers in Israel (Binibining Promised Land, 2009–10), the fact that it took place in Israel was a problem. That is an example for you of the state being too involved in terms of religious or cultural sensitivity.

Ashura (excerpt), 2012

OK: Do you know of alternative examples in (contemporary) art where religion is acceptable?

KE: There are, but I think they are coming more from the artists than the institutions. And interestingly, artists whose religiously or spiritually informed works are exhibited in and acknowledged by major institutions are often ones who have already been accepted by the art world: Bill Viola, Huang Yong Ping, and so on. I will never forget when I first saw Wael Shawky’s 2005 work The Cave in which he was almost prophetically reciting verses of the Qur’an inside a supermarket in Amsterdam. It was pretty strong and while many people were laughing at it at that year’s Istanbul Biennial, I took it quite seriously. I wondered if this work would find wider audiences. Luckily it did, but when I read texts about the work I realized only few writers actually commented on its factual importance in terms of Islam. Most read it as a sarcastic work, but years later in Berlin, when Wael told me that he had become a devout Muslim, I smiled. It was obvious. He was not joking in The Cave.

OK: Your work is also very much about ritual, but also the rituals that are involved and invoked by religion. Is this correct?

KE: More so recently. Prior to my last video work Ashura, I was examining more profane rituals, such as state rituals of the Turkish republic (I, Soldier and The Flag; 2005 and 2006) or beauty pageants of Filipino guest workers in Israel (Binibining Promised Land). However, looking back at them now, I realize that the rituals they portrayed somehow hold a connection to religion. While the former appropriated ancient, sacred rites for a deity into rituals for a ‘religion of the state’, the latter casually inserted Catholic church services into a beauty pageant, and such a twisted one! A pageant of very religious Filipino maids staged in a night-club housed in the murky depths of a giant bus terminal in Tel Aviv; a secular enclave in a country so heavily describing with a ‘members only’ type religion.

OK: Your work often involves intense proximity with subjects: friendships are formed and you are let into other worlds, as is the case in Binibining Promised Land. How do you negotiate this proximity?

KE: It grows naturally. It is part of my character to develop warm relationships with people I have only just met, especially if they are from different social strata. This is probably something I got from my mother, who as a state bank branch manager used to sit down with her subordinates at lunch instead of her co-workers. At acting school, I used to couple mostly with classmates who were almost ousted by our fancy, half-British, diva, actress/teacher. I always protected scorned drivers who were listening their music perhaps a bit too loud in their minibus against the uptight Republican ladies who couldn’t stand this ‘uncivilized’ folk music in a public transport vehicle.

It was similar with the Filipino maids in Israel. We met at the church for the first time, where I was joining the communion. Then I started strolling in their neighbourhood, a part of Tel Aviv where many Israeli friends of mine would only pass by, and a great majority of Tel Avivites simply tried to avoid. It was here I came across the poster for their beauty pageant with a mobile number on it. It only took a phone call to reach one of the most influential figures in their community. And she – James is a transvestite – gradually introduced me to the rest of the community, who all warmly accepted me as their friend. During their off days – Saturday evening into Sunday evening – we would first hang out at various makeshift churches in the neighbourhood, then go party inside that bus terminal well into Sunday morning. In between, they were performing a lot of community work as well as their pageants, so I filmed them. After deciding to do something with the footage, I asked some of the girls how I should edit the film. The scrolling subtitles – at the bottom of the video, in big pink letters – were their idea for example.

Ashura (excerpt), 2012

OK: In terms of your practice, it often involves a lengthy period of time and research. You have said it takes you roughly a year to produce a project. How does this work formally for you? What ecologies have supported your practice? Do you find this way of working difficult to sustain?

KE: Actually, it is more than a year, sometimes two, even three years; WEDDING (2006–2008) and Ashura were both two years in the making, Binibining Promised Land was three. It’s not difficult at all and I enjoy it immensely. In fact, I think this durational process is the ideal way of working on subjects like these. It’s good to go back and forth while developing the work. I mean, I used to go to Israel or the Shiite neighbourhood in Istanbul, back and forth, even after the shootings.

Work always starts with a personal curiosity and then I gradually get drawn into it. It never starts with a concrete idea. First, I observe and mingle for a long time. I don’t film during this period. When I feel we are becoming friends, at the level of being confidants for each other, then I start. Some of the most memorable moments of my life were during working with those groups. I have learned some of the most valuable things in life from them. I become emotionally attached to them. Perhaps, this is the hardest point, because after a while, we both know that I will go back to my own life. But we remain in contact, as much as possible. The Shiite community in Istanbul for example, who I made Ashura with, bestowed upon me an honorary prize in one of their celebrations this year for promoting their culture to the international community.

OK: A lot of your work focuses on marginalized characters, but I don’t think you are actually talking about their status as being marginalized, but rather, you are celebrating them. Is this a fair assessment?

KE: Totally.

OK: Have you felt that the context of Istanbul has been supportive of developing your practice or is it under-resourced? And as such, this is why you have required/needed to work in Germany?

KE: On the contrary, I think that Istanbul is actually over-resourced and very stimulating. That is why I often call it ‘Istanbul Empire’. I just needed to change cities and at that time Berlin seemed to be the most plausible option, so I went. After six years of great and productive time in that city I am moving back to Istanbul. There was only one piece I felt able to shoot in Berlin, and that was, WEDDING, about the wedding ceremonies of the Turkish/Kurdish community living there. The other pieces I have produced while being based in Berlin were all shot elsewhere and only edited there. Berlin is still an excellent place to make post-production. It always gives me that state of concentration but it is poor in action, as well as spirit. I had my first minor depression while living in that city.

OK: What institutions have been particularly useful to you, building up this practice? Have any, indeed, shaped or formed your practice or has it been autonomous?

KE: I can name three major ones, The Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (IKSV), where I worked for almost 10 years and who produce all the major Istanbul festivals, such as film, theatre and music, as well as the Istanbul Biennial and Robert Wilson’s Watermill Center, where I was an active member of the ‘core team’ who continued to work with him for many years – earlier, most artists gradually opted out. Finally,Platform (now SALT) in Istanbul, which helped a generation of Turkish artists like me.

It was at IKSV I learned different forms of art from first-hand experience working with visiting artists, all leaders in their field. I also obtained most of my production skills while working there. It was a life changing experience, which probably turned me into the communal and intercultural creature I am today. It was like the school I never had, but it was not a school. We learned through experience, not with teaching. It was so amazing that at some point I think it even went beyond Bob’s imagination. Every summer, some 50 participants, each from different countries from all over the world, would make a unique community and its effects would exceed the centre and stay with us wherever we went, for years. At Platform, Vasif Kortun also created a similar environment for local artists where experience and friendship shaped us. In that sense, was not only an art institution – it was a laboratory, with room for failure, mistakes, love, parties … the works, especially the hilarious residency floor, which was sort of a Chelsea Hotel – more than your usual residency. I think I learned more from these institutions than any school I have been to.

Köken Ergun was born in Istanbul in 1976. Ergun studied acting at Istanbul University and completed his postgraduate diploma studies in Classics at King’s College London, followed by an MA in Visual Communication Design from Bilgi University. After working with the American theatre director Robert Wilson, Ergun became more involved in contemporary art, specifically video and performance. He has exhibited internationally at various institutions including; Platform Garanti (Istanbul), KIASMA Museum of Contemporary Arts (Helsinki), Sparwasser HQ (Berlin), Digital ArtLab (Tel Aviv), the Museum of Contemporary Arts Taipei, Casino Luxembourg, Art in General (New York), and the Stedelijk Museum Bureau Amsterdam. His video work has been screened at various film festivals, including Oberhausen, Rotterdam, Sydney and Zagreb. He was the 2007 recipient of the Tiger Award of the Rotterdam Film Festival for his short film The Flag.

WHO AM I ANYWAY as pdf

Originally published by Kunsthalle Winterthur, on the occasion of the Ergun’s solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Winterthur, October 9th to November 20th, 2011

click on image below to download the book as pdf

about

My work is only finally about rituals. It is first about people. It is about large groups of people and about how they do things, collectively. My work is a journey away from the self to the group. Perhaps a quest, perhaps an escape, perhaps none, maybe both. Time will tell.